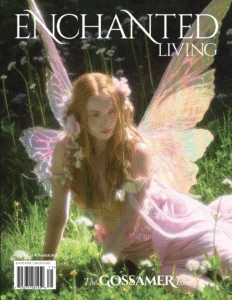

Feature Image;

Handmade glass vases by Evan Chambers Objects

It is coming on fast: one of the year’s most magical moments, a gossamer bubble of time entranced within the ordinary. And so you plan a soirée that will radiate for the solstice. You’ll celebrate light and lightness among shadows in a backyard meadow packed with daisies.

Think a bit like a daisy yourself, perhaps like Gatsby’s dashing flapper Daisy Buchanan, who is famous for asking, “Do you always watch for the longest day of the year and then miss it? I always watch for the longest day of the year and then miss it.” Your interest is the year’s shortest night. You won’t miss a minute.

You plan to begin as the daisies close their petals at dusk and end when they open again in the light. In between, diaphanous dresses will swirl through the brief hours of darkness; iridescent glassware and beads will shimmer in light from the sunset, candles, bonfire, twinkle lights, dawn. The gossamer is an ineffable extra element, the almost-not-there that reminds us not to simply look through the light, the water, the air—everything we would ordinarily call invisible and intangible—but to look at them. Touch them. Even air can take on body and substance. In its strict definition, the word gossamer refers to a loose weave of very thin fabric, like the cotton gauze with which it might share etymology (goss-amer, gauze).

Or it can refer to that thin, shimmery film that covers things like spiderwebs. But when have things gossamer ever been strict? The term is about expansion and release, shining light and being light—meaning both brightness and almost-weightlessness. It can gather all the senses and spin them into a cloud of synesthesia, so touch and vision become the same experience, sounds have a taste, colors have smells, and light and lightness entwine everywhere.

You probably need a few things, which means you have a most delightful mission to complete. It could start with a dragonfly wing or a peacock feather you find on a walk. Then a trip to the flea market, the thrift store, a friend’s attic, even a rare maybe-this-time visit to a fancy antiques mall and art gallery as you hunt for a blue glass bowl that color-shifts and shimmers as you fill it with flowers. And a veil of lace, a linen chemise, a silk dress.

You’ll honor time itself when you bring in a few special somethings to transform your space … and perhaps even yourself. The gossamer glints from the shadows or floats down from above, light as air. It is, most of all, what surprises us. A Look at Light From Both Sides Now Iridescence, for example, always seems to catch us off guard.

A damselfly’s glassy wing is all but invisible against the light as it wavers past to a riverbank and then settles in with a mere gleam of icy blue. Or a serendipitous bubble floats away, swirling pink and blue, when you set down your bottle of dish soap. The wing and the bubble contain a gossamer secret. They are transparent and almost colorless in themselves, but we still see color on them, and the color moves and changes according to the angle from which we see.

Our eyes perceive color and shimmer because we’re looking at two nearly invisible layers, and they make light start to fight itself. Most of what we see, we see because it reflects light: Light hits the object and bounces back from the surface, sending information about shape and color back to us. With transparent or translucent objects, we might also see by refraction—meaning that a wave of light enters the object and is bent or redirected, as in a prism.

This happens a lot with glass, including crystals cut especially for the job, but it’s more common elsewhere than it might sound at first. Take that errant soap bubble. It’s a sphere with air at the core, enclosed by an extremely thin wall of water with a smidge of glycerol (about one-tenth the thickness of a single hair), wrapped again by the air.

When light hits the bubble, some of it stops at the outside layer and some makes it through to the back of that very thin wall. So we see it bouncing off two surfaces at once. And the angles send different color signals; in true scientific parlance, they then “interfere” with each other—basically, they fight, and we get the rapidly shifting colors we love. Finally, the layer of water is under constant pressure from the air inside and out, so its thickness never stops changing—which produces the movement that activates the shimmer … until, eventually, the bubble bursts. When you study a clear insect wing, too, you’re looking at outside and inside at the same time. The wing is composed of two layers of chitin, the same tough, translucent material that makes up your fingernails. As a damselfly or dragonfly hovers, you perceive light bouncing off both layers, and the waves interfere with each other again.

Ordinary flies’ wings do the same trick. So why don’t all transparent insect wings shimmer in this way? Actually, they do, according to a coterie of researchers. About fifteen years ago, one group suddenly realized that they’d been looking at insect wings all wrong. When a scientist holds one up to the light, she tends to study the veins between colorless layers of chitin. When she lowers that wing and takes a moment to let a light shine on it, she understands magic.

Light interference also puts a faint shine to the transparent wings of grasshoppers. And cockroaches. And fairies. It excites the eye and inspires the heart.