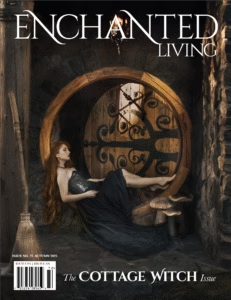

We all know the cottage. The one in the story, the one where the witch lives. It sits east of the sun and west of the moon, a stone’s throw away from a glass mountain and a quick trot from the hollow tree where three dogs howl. It’s a place of boundaries and limits and risk, the beginning and end of the story, time out of time. That cottage.

And the witch makes it … cozy? Petite, anyway. Maybe even miniature.

A dollhouse, with or without humanlike figures inside. It always looks as if she just stepped out for a second. She’ll be back before you know it, with some marvel hidden in her pocket.

We all know the witch too. She’s better than her reputation. She is a healer, most likely; a reader, certainly. Her shelves are as crowded with books as her rafters are thick with bunches of drying herbs. Or maybe (additionally?) she is a temptress and a goddess of wrath, the one who builds a home out of candy and cake and then calls us rude for tearing it to bits and stuffing our faces. Or she’s a doddering old grandma waiting innocently for her red-caped granddaughter to show up with some lunch.

Which witch is yours? Where does she live? Does she prefer to sleep in a cozy cupboard bed or a wrought-iron cot? What fills her cauldron, her nightstand, her étagère?

Yes, of course witches have étagères. They need the shelves for their supplies and the objets d’art et de vertu they bring back from their travels. One broomstick can carry a girl pretty far in a night—over the seas, maybe, or back in time about a hundred years or so.

My witch is a time traveler. She also adores tiny things. She’s a friend to the bats, and of course she loves cats (and occasional rhymes). She grows flowers for the bees and bakes cakes just because.

If I talk about her as I would a friend, it’s because to me she is Real.

Enchanted Reality

A miniaturist craves two reactions: Wow, how did you make that? And Wow, that looks Real!

When a mini lover tells you that something seems “real,” they’re talking about way more than verisimilitude. Let’s capitalize it: What’s Real is a feeling, a vibe, a je ne sais quoi that connects with the Beyond and the creator in all of us.

The Real is the otherworldly rush I get from gazing into a scene. I let my eyes go soft and a little blurry. I breathe deeply and remind myself to relax. And then I forget what size I am. I also forget the year, the date, and where I’m standing—I melt into the setting. I get to live in that suspended moment, get a taste of what it would be like to be Mary, Queen of Scots, in hiding (for example). Or the wisewoman who bandages the dragon queen’s wounds and helps her live to fight another day. Or the childless crone who watches from a window while a couple of waifs pick at the walls of her cottage and swallow gobbets of marzipan and chocolate from the place where she lives.

Just for a moment, let’s not call this Real thing a dollhouse. I prefer the term domestic sculpture. We’re talking about art on a finicky scale, a magic of transformation.

No surprise, miniaturists are wisewomen and witches themselves. We are crafty repurposers and makers of arcane little doodads that puzzle our partners and give our familiars something to bat around the floor. We are Borrowers, à la the mini people in the Mary Norton novels, taking things from the big world and making them Real. We fashion stonework out of egg cartons and thatched roofs out of faux fur; we cut up our clothes to stitch crazy quilts. And please don’t invite us to play chess. The temptation is too great—queens and knights make lovely statuary, and a pawn is a fabulous pedestal to prop up a polymer-clay sink. You would be wise to at least ask us to empty our pockets before we leave.

“I actually feel it when an item has a history—a soul, if you will,” says my friend Mark, who is building a vast Georgian mansion, one room at a time. Whether the sense of history comes from the age of the object itself (vintage is huge in the tiny world) or from the parts having done duty as something else, nostalgia helps to create a connection to a world he is both reproducing and correcting in perfect little scenes.

Mini Reality and the Fine Arts

Some of the world’s great museums display miniaturism as fine art. Denmark’s National Museum has collected over a hundred antique domestic sculptures,

and in Holland you’d probably have a hard time finding a museum that doesn’t feature a dollhouse. In the U.S., the mini capital is Chicago, where you’ll find both the Thorne miniature rooms and Colleen Moore’s fairy castle. Both deliver a Real rush, but they do it in different ways.

The Thorne rooms—a few more of which are displayed in Phoenix, a few in Knoxville, Tennessee—are the gold standard for letter-perfect reality. Narcissa Niblack Thorne was a collector and design historian whose husband was an heir to the Montgomery Ward estate.

With a bit of that five-and-dime fortune, she commissioned over one hundred of the world’s swankiest and most accurate representations of historical settings from the late 1200s to the 1940s, sixty-eight of which are now housed at the Art Institute of Chicago. Launching her project during the Depression of the 1930s, Thorne hired out-of-work artisans, designers, and fine artists to re-create great interiors from Europe, Asia, and North America: We curtsey in a gilded French salon from 1780, or we pull up a square chair in a New Mexican dining room from 1940, its white fireplace carefully shaded to show smoke damage. Admire the cubist paintings in a tiny California hallway.

You can’t help walking away from the Thorne rooms with some morsel of historical knowledge. So Thorne’s labor of love completes the mission of the Dutch baby houses of the 1500s and beyond.

Usually a tall cabinet with shelves divided into rooms, the baby house was a teaching tool: Little girls were meant to learn about housekeeping by caring for their mini rooms. (For a trip back in time to see such a house, read or watch The Miniaturist.) Almost all of the rooms are in 1:12 scale, which means that one inch of a miniature scene equals one foot of real life—the most common scale for mini creations. The same proportions suit the miniature hyperreal in Randy Hage’s faithfully gritty renderings of decaying storefronts in the New York City area—club CBGB, for example, and a favorite delicatessen, a mom-and-pop grocery. You’ll never see anything more realistically Real; you might even find that IRL seems dull and imprecise after you sink into the miniaturist trance.

As proof that a domestic sculpture doesn’t have to be realistic to feel Real, a few miles away from the Thorne rooms, you can visit a twelve-foot-high fairy castle. This is the brainchild of actress Colleen Moore, who took her dark-eyed gamine charm off to Hollywood in the 1920s to cavort across the silver screen as a flapper. The moment you see her creation, you simply fall in love; you become a different person, a more hopeful, heart-glad sort of fairy (or witch). It’s a glittering marvel that took seven years and $500,000 to make.

In contemporary currency, that’s a cost of more than $9 million—but the skills to make such a magnum opus don’t exist anymore, so, you know, priceless.

Moore was known to hand over her own personal jewels and ask that they be turned into the back of a mini chair, or maybe a diamond and emerald chandelier. Her undersea-themed library holds tiny books (usually a few lines of text spread over several pages) signed by the likes of F. Scott Fitzgerald (This Side of Paradise), Anita Loos (Gentlemen Prefer Blondes), Agatha Christie (At Bertram’s Hotel), and Daphne du Maurier (Rebecca). The astonishing confection is now on display in the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry.

The fact that these houses have a place in museums means they are continuing to educate. Through them we learn what a household is; we see how different countries and eras defined it. Architectural styles, members of the family, members of the staff, the marriage of beautiful things with practical ones. And the element of fantasy in creating a home.

My mini chum Vicky Brandt used to visit Moore’s fairy castle when she was in grade school. “I would just stand there on a stool and stare,” she says. Now she makes historical miniatures and doll clothes. “I am in control of the little world I create,” she says. “That is totally opposite to the reality we live in.”

Who needs full-size reality? I’ll take a fairy castle, a cubist painting, and one of Vicky’s frocks any day. And this song, “Garden Below, Garden Above,” written by Timothy Bailey of Timothy Bailey and the Humans during the Covid pandemic:

You held her and she spoke to you

She loves you in a miniature room, a miniature room

You live inside of the house she’s made

Outside, calamity, but inside it’s safe.

Into a Great Big Beyond

Each diminutive setting is a gesture toward something so big that it boggles the mind. Call it Art or Imagination, Beauty or the Eternal; by any name, it is a magic carpet ride into another mind, a time machine, a way of connecting to whatever in us is eternally human: our imagination.

Most of us can’t afford Thorne and Moore or Hage-level brands of transcendence, but we can and do keep pushing to think of ways to repurpose things that already exist in our lives.

So the stolen chess piece does become a garden statue, a bottle cap a mixing bowl, a dental floss dispenser the back of a sleek modern toilet.

We love kits. Especially those of us with no saw or knife skills: We’ll take the factory-milled walls and clever towers, yes, please! We might get out a Dremel and cut new holes for windows, maybe kit-bash a couple of things together and change a Victorian manor into a Castle Rackrent. To make the cottage pictured on the next page, I used a very basic kit that I bought years ago. I didn’t bash anything into it (such a term!), but I did change the precut holes to accommodate Gothic windows and a door, then filled in the extra space in the corners with balsa wood and spackle. (Remember how I said I don’t have good saw or knife skills? Not a lie.) I used joint compound to get a plaster effect on the interior walls. The wood floor started out as a $4 box of coffee stirrers that I stained four different colors, then glued down on a piece of cardboard patchworked together from old envelopes.

For every fancy, swanky, amazingly Real and incredibly expensive mini manor-castle-cottage out there, you can be sure there are dozens of makers who are doing something similar with unusual materials—meaning trash—and the castoffs of full-scale modern life. If you can’t afford the stone siding made by a high-end materials company, you can certainly afford to make your own using cardboard egg cartons, as I did here. (I think it looks more Real than what you can buy anyway, and it’s easy and fun.) You don’t even have to eat eggs; when I posted a wish for a few egg cartons, my neighbors started dropping them off by the dozen. If you are my neighbor, I’ll be happy to share, because miniaturism is also about community and joy.

The Scary Side of Tiny

But. Right. You say you happen to know somebody who loathes miniatures in all forms, who always refused to play with dollhouses and dolls themselves, even shudders at the tiny toothpaste tube that comes in a motel’s convenience pack. This person probably can’t put the feeling into words other than “creepy.” They find the Thorne rooms “creepy”! He says your sweet little cottage gives him the willies!

She refuses to let herself relax into the dreamy appreciation of things miniature!

That is, perhaps, the problem: the allure of small things, small worlds, that feel Real and yet aren’t quite real, not to our scale. They make us question ourselves and our selves and our place in the universe.

In his “Essay on the ‘Uncanny,’” Sigmund Freud described the unsettling effect of doppelgangers, simulacra, and reproductions quite simply: They make us unsure about what we call life. Amid so much that is Real but not alive, how do you know that you are alive? And that the doll who might inhabit your sculpture is not? Such questions can keep you up at night, I’ll admit.

So maybe it’s natural that there are so many miniaturists who celebrate Halloween all year long. They specialize in haunted houses and witches’ lairs. Is there anything more uncanny and disturbing than a ghost living in a dollhouse? Well, your leery friend could point out, every dollhouse is haunted—at very least by childhood ideas and games that linger long after the dollhouse stops being a plaything or an educational tool.

I imagine a tiny lady in a stiff gray frock, passing from floor to floor without a staircase, weeping for what she has lost … What has she lost? Does she need help? And what sorts of experiences has my time-traveling witch had that I’ll never share?

I give my witch all my best treasures and plans, souvenirs from the places I’ve been and even the places I want to go.

I give her some books I love and others I want to read. Her cottage is my diary and day planner.

What we see in a domestic sculpture might be Real and recognizable, but it isn’t entirely little-r real. No matter how meticulous the mini work is, we know there will be some little detail that jars you, something that seems wrong.

The thickness of the writing on a jar of eye of newt, for example: From the perspective of a 1:12 person, it looks like a spluttery attempt by a kindergartner.

Most commonly, we notice that our fabrics are all far too thick to move properly in curtains, carpets, bed hangings; even all the geniuses of the Thorne rooms can’t quite make the drapes look entirely real.

And that can be alarming. Maybe we were just about to surrender to the illusion and live imaginatively (as I truly believe I could) as a miniature person in a wistful Gothic cottage, but then we see that the small world is different. Ordinary reality whooshes in and plucks us back.

I, for one, would love to rid myself of that reality.

The miniature world beckons. How far in you let yourself enter is between you and your psyche.

“All the things real people couldn’t have”

As Colleen Moore said when she was planning her spectacular fairy castle in the midst of the Great Depression, “We’ll have to think of all the things real people couldn’t have.” That’s the purpose of miniaturism: making what’s impossible in the real world into a deeper Reality, using whatever comes to hand.

In the Thorne collection, each roombox hints at a vaster world. A door opens into another room, barely glimpsed, or a dramatically curved staircase; a window offers a hint of tantalizing view. You think, This could be my room, if only I could shrink down …

Which world is Real and which simply real?

Build the cottage.

Be the witch.